Tear down his statues if you will, but Sir John A. Macdonald could not be an architect of Canada’s policies towards Indigenous people – he was far too drunk.

Or so I allege, Canada the good, in this intervention.

No doubt John A. grumbled consent, sometime between hang-over o’clock and noon. But, if you want the truth about Canada’s founding policies towards First Nations and Metis (mixed-race) people, you might want to take a look at the more likely architect. That would be John A.’s right-hand man, brother-in-law and expert enabler, from a family of colonial right-hand men, born on a slave-owning plantation in Jamaica, one Hewitt Bernard.

I was doing some Internet research into the history of a friend’s property in Jamaica. I was surprised to find connections to multiple important events, but the biggest surprises were the connections back to Canada and the Red River settlement (today’s Winnipeg and surroundings).

The most interesting event, and one which Canada continues to deny, suggests Hewitt Bernard was following the playbook his relatives and associates used in a colonial atrocity in Jamaica a few years before.

The story that follows is roughly in the order in which I found it. Perhaps historians would put it in a better order – I am not a historian. I am a concerned citizen, attending an intervention for a beloved nation still in deep denial. I wasn’t researching Canada, but I stumbled on the story of how the Canadian West was won, or stolen, or purchased, or bungled, or whatever it was depending on who you ask.

Folly Estate

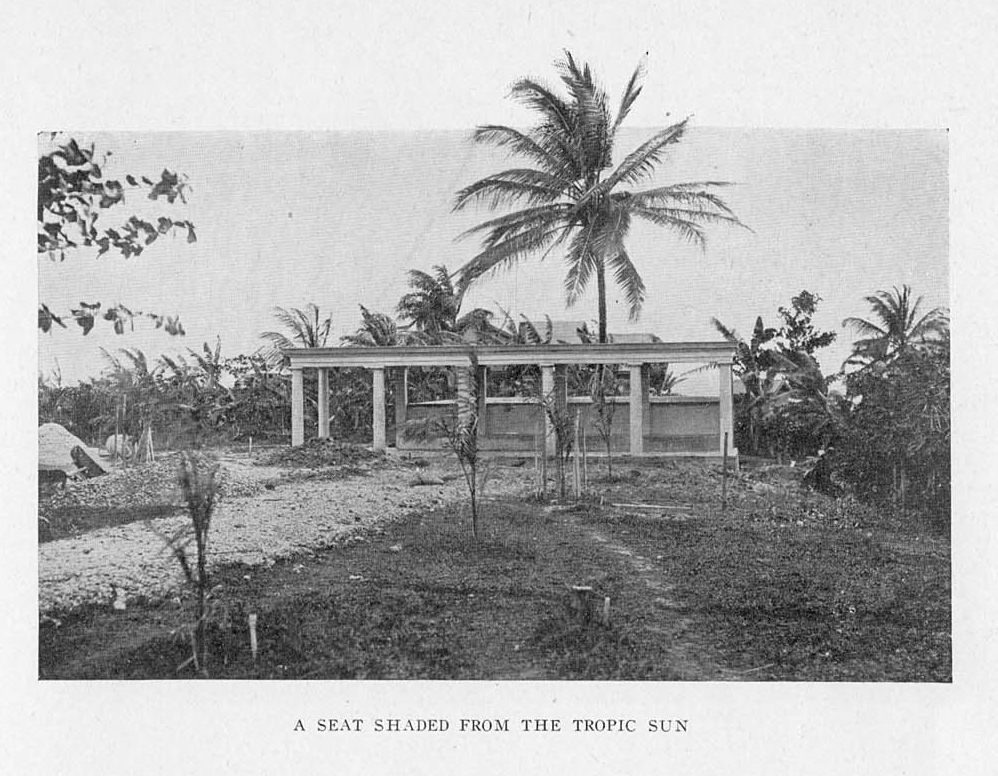

I am a fan of reggae music and know Glen Williams and his band from Winnipeg. I was planning a winter get-away when Glen invited me to his family home in Jamaica, on a corner of “Folly Estate” in Port Antonio. There I met Glen’s parents, Louise and Ronald.

Ronald was retired from working for the Jamaican government. Upon Jamaican independence in 1962, his job included spreading the news to the Maroons, that the British had finally left after three centuries. The Maroons are descendants of escapees from Spanish slavery during the British takeover in 1655, and probably, indigenous Taino people who are sometimes declared extinct. Ever since, the Maroons have been living in hidden communities in the jungle of the mountainous interior, vowing never to be enslaved again.

Centuries ago the Maroons became the only non-white foe to defeat the British army. They won the right to their own lands and laws, except in cases of murder, and in return agreed to fight with the British against foreign invaders. They won using local knowledge, baffling camouflage, and the military leadership of Queen Nanny, now a National Hero of Jamaica.

And while the Maroons lived mostly in peace, they were an irritant to the government of British Jamaica, leading to an inordinate amount of debate and legislation. There was constant suspicion that the Maroons were stealing British property, including fruit from plantations, and humans who escaped enslavement.

Many Maroons have long-since integrated into Jamaican society, and there are now roads to the main settlements. But in 1962, Ronald Williams traveled jungle trails to spread the official news as far as he could, and exchange agricultural information for the Maroon’s incredible knowledge of jungle plants. Some knowledge, about plants not found in Africa, is so complex it can only have come through the Taino (like the seven non-obvious steps for making chocolate).

Ronald showed me some examples of plants from Maroon territory in the Blue Mountains. He also showed me several specific historic sites around the property, including the last remaining folly of at least three on Folly Estate. A folly is an elaborate or ancient-looking building with a mundane purpose, or no purpose at all beyond flashing the cash. Now in ruins, except for the Williams family home, Folly Estate was at its grandest over a century ago.

And there is a grave. Of a preacher, according to Ronald.

Some years have passed, and with the death of Glen’s parents, the future of the family home is in question, as is the preacher’s grave. It seemed like an interesting puzzle – to find out who was in the grave, and unfortunately, time to do so may be short.

Morant Bay, Jamaica, 1865

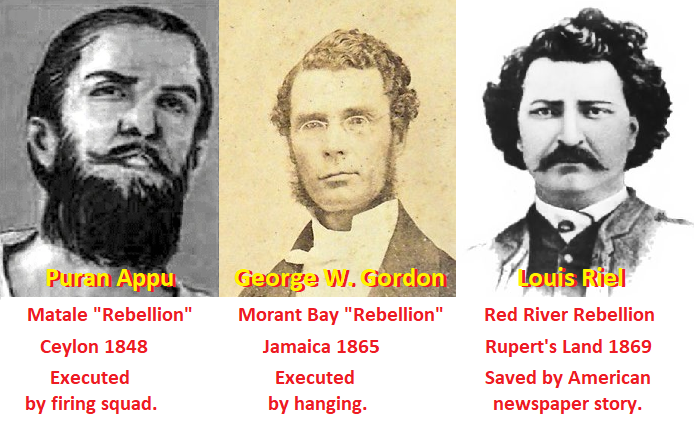

There are two former owners of the property who were preachers. Finding out more revealed they were both among the very few witnesses to survive the colonial atrocity known as the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865, although “rebellion” is not the correct word.

It all began with land, and accounting.

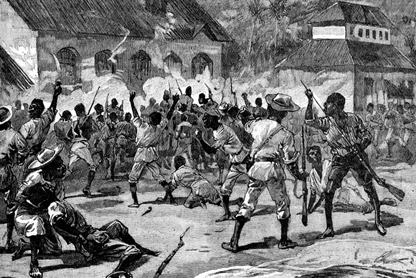

What started as a protest march by black citizens of Jamaica, to see their Governor about land reform, turned ugly, and then uglier, and then ugliest when the British Army went berserk. Along “eight miles of bodies”, hundreds of black children, women and men were shot dead for the crime of being seen by a soldier from a section of the road between Port Antonio and Morant Bay. Hundreds more were arrested under martial law, and kangaroo courts quickly sorted the guilty to be executed, from the innocent to be flogged.

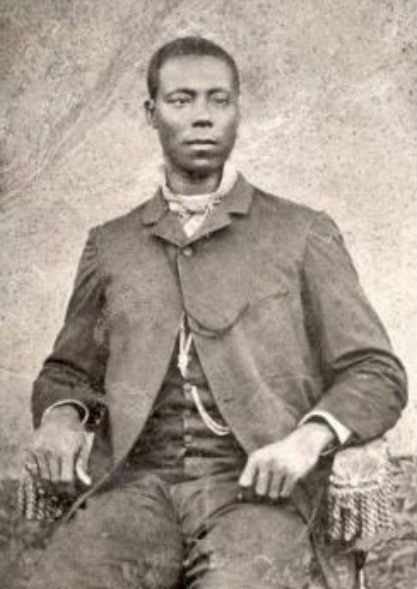

One of our preachers in question, Reverend James Service, was mentioned in the British parliamentary inquiry that followed, because he was arrested but not charged, and stranger still, not flogged. He was a black Baptist preacher, which was crime enough for the white Anglican establishment in Jamaica. Jamaican National Hero Paul Bogle led a protest march and was framed for several crimes, executed and demonized. Bogle, Service and perhaps the other preacher who could be in the grave, were neighboring preachers serving the east end of the island.

The parliamentary inquiry records three verbatim copies of a letter signed by the possibly functionally illiterate Bogle, but they differ slightly. Also, the letter seems to have been found a day before it was written. The original forgery is lost, or held by the United Kingdom and not available for study. The copies implicate both Bogle and the Maroons. An alleged agreement between them to wage war on whites, followed later by a supposed betrayal, is taught in Jamaica to this day, and is the basis of some lingering historical resentment. The story is incomplete and on shaky ground.

The parliamentary inquiry didn’t delve into the truth about Bogle, or the experiences of Reverend Service and other blacks, for several reasons. First, most black witnesses were dead. Second, most white witnesses were guilty. Third, the inquiry was focused on another question entirely – why was George William Gordon illegally kidnapped, transported on a British Navy ship into an area under martial law, arrested there, tried without counsel or defense, and executed in the Queen’s name? You see, he was a leading taxpayer, and spilling his blood ultimately meant red ink in Her Majesty’s Jamaican accounts.

Another future Jamaican National Hero, Gordon was taken from Kingston to Morant Bay on the deck of the British warship Wolverine, which first took a long detour to Port Antonio and anchored near Folly Point – Glen’s place, owned by Reverend Service at the time. I like to imagine Service’s choir gathering on the harbor shore on a quiet night to belt out some hymns for Gordon, maybe slipping in some messages only a fellow Baptist would understand.

Gordon’s crimes began with being mixed-race, but everything about him made the governor furious. Rich, handsome, with a lively step and a quick smile, Gordon was a popular man-about-town. For the most part, he was self-taught, and learned “ready business habits” and accounting while working in his uncle’s store.

After slavery, the white merchants of Kingston allowed only whites into their stores – because of racism and because whites had all the money. Gordon welcomed everyone into his store – good credit, Bad Credit, NO CREDIT – cRaZy George made up for it with VOLUME. But seriously, Gordon understood accounts, and by extending credit to hard workers he became merchant and de facto banker to 90% of the population.

This mixed-race self-made man became the wealthiest citizen of Jamaica, while established white families struggled. At one point he paid all debts to save his father’s estate, which he was never invited to visit.

Although very few black citizens were able to meet voting requirements, which included owning land and paying taxes, Gordon was elected to the Assembly where he was a voice for the oppressed. The poor needed land to feed their families, and to pay taxes someday. But the law kept them from harvesting fruit that otherwise rotted away on abandoned plantations. He was also supporting Baptist churches, and worse, black preachers such as Paul Bogle and James Service, although he never completely turned away from the establishment Anglican church.

Governor Eyre just had to find a way to get rid of him.

Eyre did, but it led to the parliamentary inquiry and his firing. Eyre was praised for decisive early action, but one question remained for historians – why did he over-react and prolong the incident? An angry mob, which got angrier when shot at, had mostly calmed down after a few days. Order had been restored in Morant Bay by black citizens. It was then that British soldiers arrived and went berserk, and what had been a bad incident became a weeks-long atrocity.

The more I learned about Gordon and Morant Bay, the more I was reminded of his contemporary Louis Riel and Red River. But a closer look at Governor Eyre took me to an earlier historic event that connected all the dots to Canada, so, let’s rewind the tape a bit.

Ceylon, 1848

It all began with land, and accounting.

The land was Ceylon (Sri Lanka today), which the British gained from the Dutch East India Company in the treaty of Amiens, 1802. That gave them the ports and land around the coast. The interior kingdom of Kandy had to be taken by force from families that had lived there for generations.

As for accounting – there was a large stack of cash in the safe of the British governor in Ceylon. The stack was made up of extra bank-notes, printed and sent along to Ceylon just-in-case, and entered in the books as an asset.

A new governor, Lord Torrington, was being sent out by Her Majesty Queen Victoria. At the age of 35, with no relevant experience whatsoever, Torrington’s only qualifications were being a cousin of the British Prime Minister, and a keen interest in accounting.

Upon seeing Ceylon’s books, Torrington immediately understood that the bank-notes in the safe were not backed by silver, gold, the Queen’s promise, or anything at all. So, if they ever left the safe, these spares were a liability to the Crown, not an asset. Bottom line – Ceylon was broke, and young Torrington was on his way to the rescue.

His cousin the Prime Minister may have been hedging his bets when he chose some top aides to accompany the vice-regal, to fill in knowledge gaps, like how to run a nation, and, where’s the gin? Among the entourage, acting as personal secretary and advisor – Dallas Bernard from Jamaica – the first appearance of a Bernard in the story.

Colonial Ceylon had been financed through duties on shipping and trade, a business the Dutch previously found quite profitable. To fix the mess made by the British, Torrington would directly tax everyone and their dog – literally. Any dog found on the street had to prove they paid their taxes, or come up with cash on the spot. Failure to do so resulted in arrest, and a stint in doggy jail. I don’t know if they were given one bark to call their owner, but if someone didn’t bail them out, the sentence was death.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. I’m being silly – dogs didn’t carry cash back then. I know. The point is – the Kandyans didn’t either. They had to pay taxes in cash, but they had no access to cash – they lived by barter. They had to show documents to prove they owned their family’s home, but no such documents ever existed – everyone in the community knew who lived where.

So it’s not me being silly. As silly as Torrington may have been, he was surrounded by competent colonial administrators, such as Dallas Bernard, so there had to be some method to the madness. It is one thing to impose heavy taxes on the poor; it is another thing to spend money trying to collect money you know doesn’t exist.

For Bernard, the situation was familiar – Jamaica and Ceylon were island nations with mountainous interiors inhabited by troublesome people claiming land. The people were angry they could not pick fruit before it rotted away on plantations owned by speculators in London.

Bernard would probably not want Ceylon and the Kandyans to go the way of Jamaica and the Maroons. He was likely among the majority of white Jamaicans not happy with the Maroons’ special status. There was some long-held embarrassment that the British army had given-up a few days before the starving Maroons would have, and long-term frustration that the government had to deal with them at all.

Bernard had first-hand experience with the Maroons – one of his properties was high in the Blue Mountains bordering Maroon territory. Today, Jamaicans are happy to tell you that the best coffee in the world is grown there, but after slavery, Jamaican growers were finding it very hard to hire workers previously motivated by the whip. The higher the pay offered, the shorter the formerly enslaved would work – they only needed a few coins to get by, and once they had them they were gone, to work their own small squatters’ plots to feed their families.

In Ceylon, the British had fought for decades to secure the interior. Eventually, traditional leaders were killed or bought off. The intricate ancient irrigation systems and rice paddies were destroyed to grow coffee. But the people were still there, and they refused to work on the new plantations even though they faced starvation. A new kind of revolt was brewing, which saw popular leaders rising from the ranks.

Gongalegoda Banda rose from humble beginnings to lead a protest march, and shortly after, to coronation by a leading Buddhist monk, as king of the remade kingdom of Kandy. Puran Appu was appointed the equivalent of Prime Minister, presumably because he had some idea of what to do next.

With only a primary education followed by a decade traveling Kandy, Appu learned about colonial laws and bureaucracy while staying with an uncle who worked with the British. During his travels he become a dashing Robin Hood hero-outlaw figure, and very popular.

What the new kingdom did next was to gather several mobs to swarm hated British buildings, such as the tax offices. The pen is surely mightier than the sword, but one accountant did a quick calculation of the might of his one pen versus the mob’s many swords. Making a retreat to tax another day, he was forever branded a cowardly traitor to the British empire.

I think the ridiculous taxes were intended to provoke outrage and protest, which they did. I think the soldiers fired a few potshots into various crowds to provoke violent responses, which they did. I think the goal was to manufacture an excuse to declare martial law, which Torrington did. With martial law, British soldiers could round up rebel leaders for immediate trial and execution, or keep it simple and just shoot whomever, which they did.

The soldiers were not English boys though, they were a company of ethnic Malays from another British colony, across the Bay of Bengal. No sense putting whites in danger, and sowing divisions between ethnic groups within the empire was a bonus. With the dogs of war completely unleashed, predictable atrocities followed. Appu was betrayed and captured, tried by a kangaroo court, and executed.

King Banda proudly pleaded guilty to waging war against the Queen, but because killing a king might rile up his subjects again, his death sentence was reduced to 100 lashes. Unfortunately his wounds from the lashes were so bad he needed immediate medical attention at the nearest best hospital, on the Malay peninsula, far across the Bay of Bengal. Unfortunately, as a prisoner, the customary spot for him during the ocean voyage was the open deck. Unfortunately, he died months later.

You’d think one of Torrington’s advisers would have known the journey would be torture and lead to a drawn-out but certain death. You’d think.

With their popular leaders gone, the rebellion fizzled out. But lingering reports of extreme brutality under martial law made it into London newspapers. Parliament was forced to investigate, and while they praised Torrington’s decisive early actions, they found he went too far, for too long.

Party On

Torrington was disgraced and lost his job. Dallas Bernard emerged unscathed, with other administrative postings around the empire to follow. But Torrington had no problem finding supporters among good men of the empire, who were happy to put him up, throw a party, and toast him for putting the empire before personal ambition. Among his supporters was BFF, Edward John Eyre, future Governor of Jamaica.

Torrington emerged with one message – the last words of Puran Appu in front of the firing squad, who claimed that with just six good men to lead, there would not be a white man left in Ka..BaBaBang! This had shaken young Torrington, who claimed the island was nearly lost, and dined on the story for years. He had no experience or training to support his conclusion, nor would any self-respecting British officer support it, but they enthusiastically toasted him for putting empire first.

Both men’s claims were nonsense, vastly over-estimating the threat. Unlike the Maroons, the Kandyans had no chance against the full might of the British. It was a different century, a different terrain, a different people, and they had no Queen Nanny. Maroon-like guerrilla warfare was the Kandyans’ only chance, but all traditional leaders, including military leaders, had been killed or bought off. Swarming tax offices did little but raise unrealistic hopes. Like everyone else, Torrington was taken in by the dashing Puran Appu, and the high drama of his demise.

Victorian parties included guests performing for other guests – poems, music or small dramas. A first-hand story of high stakes danger and intrigue would be the highlight of any party. For audiences back then, I bet Torrington’s performance, with some rehearsal and embellishment, was as gripping as any Errol Flynn, Harrison Ford, or Johnny Depp movie.

It seems to me there is a simple explanation to the question of why Eyre over-reacted during the Morant Bay atrocity. Seeing his friend’s act, I think Eyre too was swept up into thinking that with six good men to lead, Puran Appu or George William Gordon could take a country.

Eyre followed his friend’s lead closely. He refused to meet with citizens with legitimate grievances over land and the administration (or lack) of justice. He had soldiers escalate protests until there was an excuse to declare martial law. He sat by as soldiers committed atrocities against innocent citizens. He allowed kangaroo courts to waive all normal rules of law and decency. He was praised by parliament for decisive early action, but lost his job for going too far, for too long.

Eyre’s legacy was a lasting division from having one ethnic group do some dirty work against another. You might remember that Gordon spent time on the deck of the Wolverine, anchored near what is now Glen’s place. You might wonder, why? Why risk having someone swim out to attempt a rescue from, say, the Reverend’s place? What was more important than the swift delivery of Gordon to injustice?

Well, it was delivering guns. Guns were taken from Port Antonio, south to the Maroons along the same jungle trails Ronald Williams would later travel. By old treaty, the Maroons, who kept their word, were to fight with the British against foreign invaders. But, there were no foreign invaders, so the Maroons were lied to.

When a group of armed Maroons encountered Bogle by chance, Bogle offered no resistance and went with them to town and his fate. Whatever the Maroons were told, the British sowed lingering divisions while avoiding a jungle fight that English boys in red uniforms weren’t good at, for some reason.

Governor Eyre suffered the same fate as Governor Torrington – he was forced to join his buddy on the party circuit.

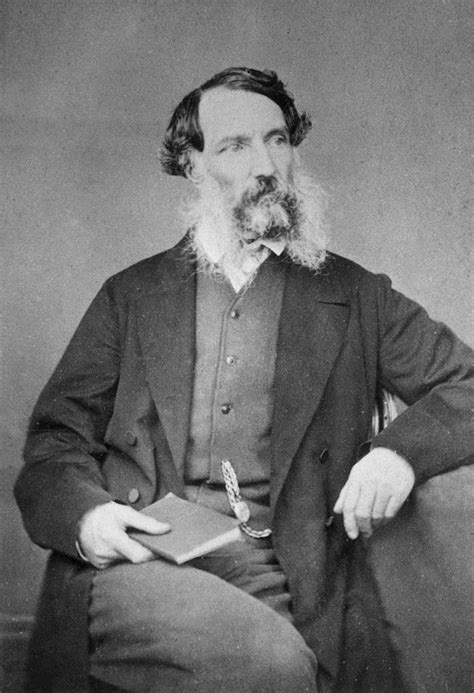

Hewitt Bernard

The Bernard family’s last profitable year was 1834, when Hewitt was in his early twenties. They received 1,613 pounds in contested compensation for losing ownership of 85 humans (about $3000 per enslaved person in today’s Canadian dollars). Their plantation was within walking distance of the governor’s mansion in Spanish Town, and Spanish Town was the capital because it was in the heart of the best agricultural land. Even so, the family fortune declined sharply.

The plantation’s location reflected the family’s proximity to political power as well. Hewitt and Dallas were not immediate relatives, but came from the same well-established family with a history in Jamaican politics and administration. They seemed to have the same political skill set.

Hewitt missed the chance for some good old father-son bonding at the slave auction, just as he became old enough to bid for his own humans. He eventually decided to try his luck in Canada.

In Canada, Hewitt Bernard met a charming drunk who was doing well in colonial politics. Hewitt proved an expert enabler and knew exactly how to get his man to the very top, including finding a suitable wife for the drunk – Hewitt’s sister Sarah. In return for his hard work, he got to be architect of a country whenever his boss was on a bender, which was most of the time.

Allegedly. I could be wrong. Prove me wrong, Canada. It’s easy – release all relevant historical documents held in secret to this day, to prove once and for all, that John A. was a social drinker who got a little tipsy a few times, but was always on the job.

Oops, excuse me, I just snorted out loud.

Canada, I love ya, but I ain’t buying the story that John A. was drunk occasionally and sober most of the time. I want proof it wasn’t the other way around – because I’ve been around the block a few times. His enabler set your founding racist policies, and you are in denial.

Now I realize that I only have circumstantial evidence – some family and business connections. Did I mention that Hewitt’s former law partner was the supreme kangaroo of the Jamaican courts during the Morant Bay atrocity, Judge Edward Kemble?

That doesn’t prove Hewitt was a racist or following Kemble’s lead, but it would explain a curious incident during the Red River Rebellion.

Red River, 1869

It all began with land, and accounting.

The land was Rupert’s Land, a vast part of Turtle Island (North America) claimed by the Crown and owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The North-west was rapidly changing, and it was time for company management to be replaced with proper civil government.

This was to be done by transferring the land from the Hudson’s Bay Company to the government of Canada, in exchange for 300,000 pounds (about $50 million in today’s Canadian dollars). It was all just accounting, because there was no battle to be fought, treasure to be moved, not even an election to be won. On December 1, 1869, the transfer would take effect in the books of governments and banks in Ottawa and London. Queen Victoria would see her colony expand its territory, and, as a major shareholder of the Hudson’s Bay Company, she would get a nice little dividend to buy some more black dresses.

News of the upcoming non-event was concerning to the Metis living at the Red River settlement. It was the land they were farming that was being sold, but they weren’t seeing any of that money. No one was asking their opinion. No surprise here – indigenous First Nations’ claims were dismissed entirely as “pretend”.

Some American politicians wondered if they could submit a higher bid. US Secretary of State William Seward was certainly interested, but over-paid for Alaska. If he hadn’t, he might have had enough to beat Canada’s bid. Of course, the British would not have accepted this, but…

Almost all new settlers were arriving through the United States – which meant a bumpy wagon ride past the end of the railroad to a comfortable paddle-boat on the Red River at Fargo or Grand Forks. That was much easier than the northern ocean route, or the wilderness canoe route from Canada far to the East. Americans felt the people should vote on such a momentous change, and more and more of the people were Americans. They had a chance for a few years, before Canadians could build their own railroad.

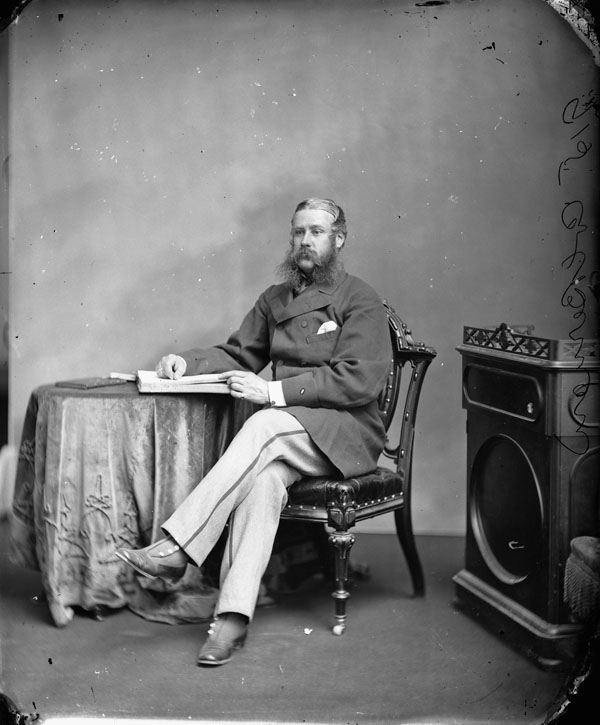

William McDougall was Hewitt Bernard’s frequent dinner companion at Lady Sarah (nee Bernard) Macdonald’s table, and was chosen to go to Red River through the territory and courtesy of the United States. He would declare the North-west a colony of some sort, of the colony of Canada, and himself Lieutenant Governor. According to entries in Canada’s books, his luggage included 350 Spencer and Peabody rifles – not sure if President Grant knew about them when he graciously granted passage. Along the way there were concerning reports of nearby liquor smugglers, especially concerning because there was nothing illegal about liquor or its transportation.

But then a newspaper in Minnesota published what they claimed was McDougall’s secret plan, which was essentially Torrington’s and Eyre’s playbook. Protest would be met with a few bullets, leading to a violent response, leading to declaration of martial law, some general mayhem, then rounding up of rebel leaders followed by quick trials and executions. Instead of Malay soldiers or Maroon fighters, McDougall would see if First Nations warriors would do the dirty work if given money, guns and lies.

All this terrified the people of Red River, and also Americans because they feared an escalating war would not stop at the border. The events in Jamaica were no secret in Red River or Minnesota. When they heard ‘governor’, they thought of Governor Eyre, martial law, and miles of bodies.

The Canadian government’s line was, and still is, that there is nothing to the story, but that would make it out-of-character for the newspaper. Besides denying everything, the politically expedient thing for Canada to do was throw McDougall under the bus, or whatever the equivalent was back then, and for John A. to sober up – he was in danger of taking the fall, Bernard was safe.

McDougall was a liberal in a conservative cabinet, and communications were slow, so it was easy to throw him under the ox cart – just delay the accounting, and nobody tell McDougall. He was supposed to figure out there would be a delay because of a newspaper story. There were no plans to consult anyone at Red River. No accountants would face a mob. There was no reason to delay, except to sacrifice McDougall during a hasty switch to plan B, while plan A was slowly cleaned up.

On December 1, McDougall declared that the Hudson’s Bay Company was no longer in charge of Rupert’s Land. He may have had the power to do this, but even if not, there was no way to undo it. He quickly followed with the declaration that Canada, as rightful purchaser, was now in charge. He definitely had no power to do this because the purchase was delayed, so in effect, no one was in charge, giving Louis Riel a reason to do the proper thing and set up a provisional government.

Back in Ottawa, the story was – McDougall was incompetent and had gone rogue. Maybe he had too much scotch and cigar smoke at his last meeting with Hewitt Bernard just before the taxing journey.

So that is it, just circumstantial evidence, possibly just a coincidence that it aligned with previous atrocities, possibly early sensational journalism. There are some crucial documents that might clear things up, but they are not available to historians.

Oh, just one more thing

Why is there an entry in Canada’s accounts showing the cost of rescinding an order given to Colonel John Stoughton Dennis, known to exceed his authority when there was a chance to start a fight? Some soldiers said the order was to take a wagon-load of guns and cash south and find the Maroons – excuse me, I mean – west and find the Sioux, and do with the wagon-load as he saw fit. The accounts show the Colonel had given somebody a wagon, and Her Majesty desperately wanted her wagon back.

I see Dallas Bernard’s, Governor Torrington’s, Governor Eyre’s, Judge Kemble’s and Hewitt Bernard’s paw prints all over this one. The plan was for a third atrocity, and Canada duly authorized Colonel Dennis to get it started, until the whole thing appeared in an American newspaper. Even in failure, talk of Canada’s plan A led to lingering divisions between Metis and First Nations, English and French. To understand the lasting impact, and Canada’s founding policies towards First Nations and Metis, check out the politics of our nation’s first prime enabler.

As for the original mystery – who is in the grave? Glen will soon be back home in Jamaica for a closer look at the grave-site. It is probably occupied by a witness to an atrocity almost repeated in my hometown in Canada. I am left wondering how I ended up at a far-away grave, to receive a puzzle leading to the almost forgotten story of its occupant, the surrounding people, and some of my relatives.