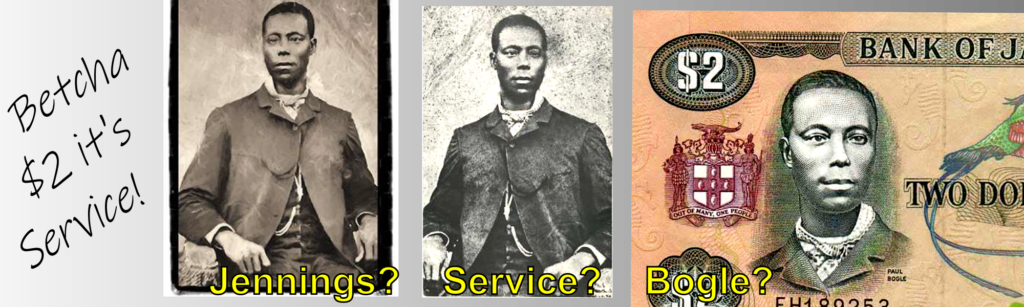

Every so often it is revealed that the accepted photograph of Jamaica National Hero Paul Bogle (1822-1865) may not be of him. That is because the same photo is used for Thomas Jennings (1791-1876), the inventor of dry cleaning and first African-American to be granted a patent.

This was known when Bogle’s memorial sculpture created controversy because it is based on his descendants and not any portrait; when noted in the Gleaner in 2012; and, now with arguments circulating on the Internet.

The controversy of who is in the photo has divided proud Jamaicans and American Black History activists for no reason, because both sides have convincing arguments the other is wrong. So the photo is not of Bogle nor Jennings. The sitter in the photo is more likely the Reverend James B. Service of Boston, Portland, Jamaica, than either of the more famous contenders.

The argument against it being Jennings is his age. The invention of the daguerreotype photograph was announced to the world in 1839, when Jennings was 48. Previous to that, good portraits of living people were impossible because exposures took hours, not minutes.

There is a clue in the arm-rests visible in the photo — they are fringed. This upholstery style became fashionable in the 1860s. Although far from conclusive, this suggests a later date, when Jennings would be closer to 70. The sitter in the photo does not look to be anywhere near this age range.

The argument against it being Bogle is mostly that it does not match his description, or his age if photographed in the most likely 1860s range. History records little or nothing about him before the Morant Bay “Rebellion”, and he did not survive, so most of what we know comes from British records. The British portrayed him as a monster, making it a challenge for historians to form a realistic portrait of the man.

The notice of a reward for his capture may have the most reliable description, as authorities at least had an incentive for him to be spotted in a crowd. He was described as “A very black man, with shining skin, bearing heavy marks of smallpox on his face, and more especially on his nose; teeth good, large mouth with red, thick lips; about five feet, eight inches in height, broad across the shoulders, carries himself indolently, and has no whiskers”. The man in the photograph appears to have smooth skin and a slim build, and would simply not be picked out using the description.

Both sides are right, so both sides are wrong because the gentleman in the photo is someone else entirely. A mistake was made at least once, so it could easily have been made twice in different locations because of human nature. Someone wanted the photo to be of the historical figure they were researching, and with no other portrait and only circumstantial evidence, desired authenticity became accepted authenticity over time. It is only human.

There is, or was, a note attached to the supposed Bogle photo in the Jamaican National Archives, which suggests this happened: “W.G. Ogilvie, a member of the Jamaica Historical Society, has discovered a photograph which, although it has not been absolutely authenticated, appears genuine”. Without any further explanation this is absolutely not conclusive, or even of much use, but suggests someone wanted it to be. It might have been in a box with an ambiguous label from the right time period and area, or something else suggesting it could be Bogle, but also any number of others. We don’t know.

The same could have happened with Jennings. Not only was he an inventor, he went on to use his considerable earnings to fight slavery in America. He was active in the Abyssinian Baptist Church of New York City, which was an early black-led church. The church was and remains at the forefront of African-American politics, which at the time meant ending slavery in the Southern states.

Despite Jenning’s fame and fortune, there is at most one known photograph of him; but it shows a young man, so it is not him. At some time, someone must have been looking through his papers or old church records. Upon finding a photo of a young man, which might even have resembled the memory of the old man, it is only human to want to believe it was Jennings (link to a better explanation I didn’t know about. It refutes some of the following, but I think the truth is somewhere in the middle).

It had to have happened something like this once, and likely twice, although the details may never be known. But this raises an interesting question — who else could it be? Millions of photographic portraits were taken all around the world between 1840 and the 1860s. Without further evidence, beyond the images themselves, it is impossible to do more than speculate.

So, let’s speculate a bit, for fun. Of course the sitter could be any young black man from the time, or there could be a less random connection. There seems to be one strong connection between Bogle and Jennings — black-led Baptist churches. It is reasonable to speculate that the sitter was also associated with black-led Baptist churches. He appears to be around 30 years-old, so a best guess would be that he was born around 1830.

Another clue is that a photograph of the young sitter was taken at all, and then duplicated, so old copies could be found later in both Jamaica and New York. Daguerreotype photographs resulted in mirror-images of the real world, which could be corrected with the added complication of a real mirror. A common way to make copies was to take a picture of the original, which would flip the image back, so it is not a surprise to find both versions. The correct orientation can be determined from the buttoned side of men’s coats (which was somehow reversed again in the image on the $2 bill, putting him in a lady’s coat).

Then in the 1860s, the ‘carte de visite’ photo cards became popular. For the first time there was an inexpensive way to get 8 prints of a photo at once, and it started a fad. It was like trading baseball cards, except instead of athletes the cards might be of ordinary people, or at least people who had a little money to get in on the fad. Or they might be of someone a little more famous, or wanting to be.

One sub-genre of the fad was the realistic portrayal of well-dressed successful people of African descent, to combat the ridiculously racist drawings which too often appeared in newspapers of the time. Another part of the fad survives to this day — the school or graduation photo. Setting up once, to take photos of a parade of students, and then making multiple copies of each, made economic sense then, as it does now.

One possible scenario is that the original photo was taken in Jamaica, and multiple ‘carte de visite’ copies were taken back to New York by missionaries, to show Americans the successful results of their financial contributions to education in Jamaica. One likely school would be Calabar Theological School, Trelawny, Jamaica, which was training young black men to lead black congregations, and was supported by Baptist congregations in America and Britain. One likely star student was James B. Service.

Born in 1831, James Service later led a church he called “Tabernacle” and built a home he called “Reward“. Numbers 18:31 of the King James Bible says “… it is your reward for your service in the tabernacle…”. I think he may have felt more of a personal Biblical calling than the average student.

He was arrested without charge during the Morant Bay atrocity of 1865. He was impressive enough at the age of 34 that he talked his way out of jail, when very few did. As a fellow black preacher with Bogle in eastern Jamaica, Service spent anxious hours wondering if he would meet Bogle’s fate, but was released with an apology instead of the customary flogging. Soldiers did make a mess of his house, including his wife’s private garments, and his horse was confiscated and returned lame. Service’s loyalty to the crown and his beliefs never wavered, although he no doubt witnessed brutality.

Reverend Service is the subject of the Patwa saying “Ah no so Savis did get Folly”, a reference to his frugality, which enabled him to buy up properties on Folly Point, Port Antonio. He was preaching at a time when bananas first put cash in the pockets of many of the formerly enslaved. Sugar plantations must be large to keep boilers stoked, freshly supplied and profitable, but the farmers who stayed away to work their own small squatters’ plots could get cash for bananas anytime, at the wharf in Port Antonio.

With cash came temptation, so if the main message of Service’s sermons was frugality, he was the right man in the right place at the right time. His plans for Folly Point were likely similar to others of the time — to provide good land to black Jamaicans. There is evidence he was thinking of a co-operative farm, and his views and works were certainly of interest on the island and beyond, before and after Bogle’s spectacular but brief time in history’s spotlight. Service did assemble a large tract of land which later became Folly Estate, and he may be buried near the Williams family’s historic cabin there.

Did James Service actually sit for the photo that ended up on Jamaican currency? I have no evidence he did, but that is more than can be said for Bogle or Jennings, who did not. If it was James Service, or someone else with a similar story, he deserves his place in history and especially on currency, as one of thousands who dedicated their lives to improving our lives, but whose memory is in danger of being lost, forgotten, or confused.